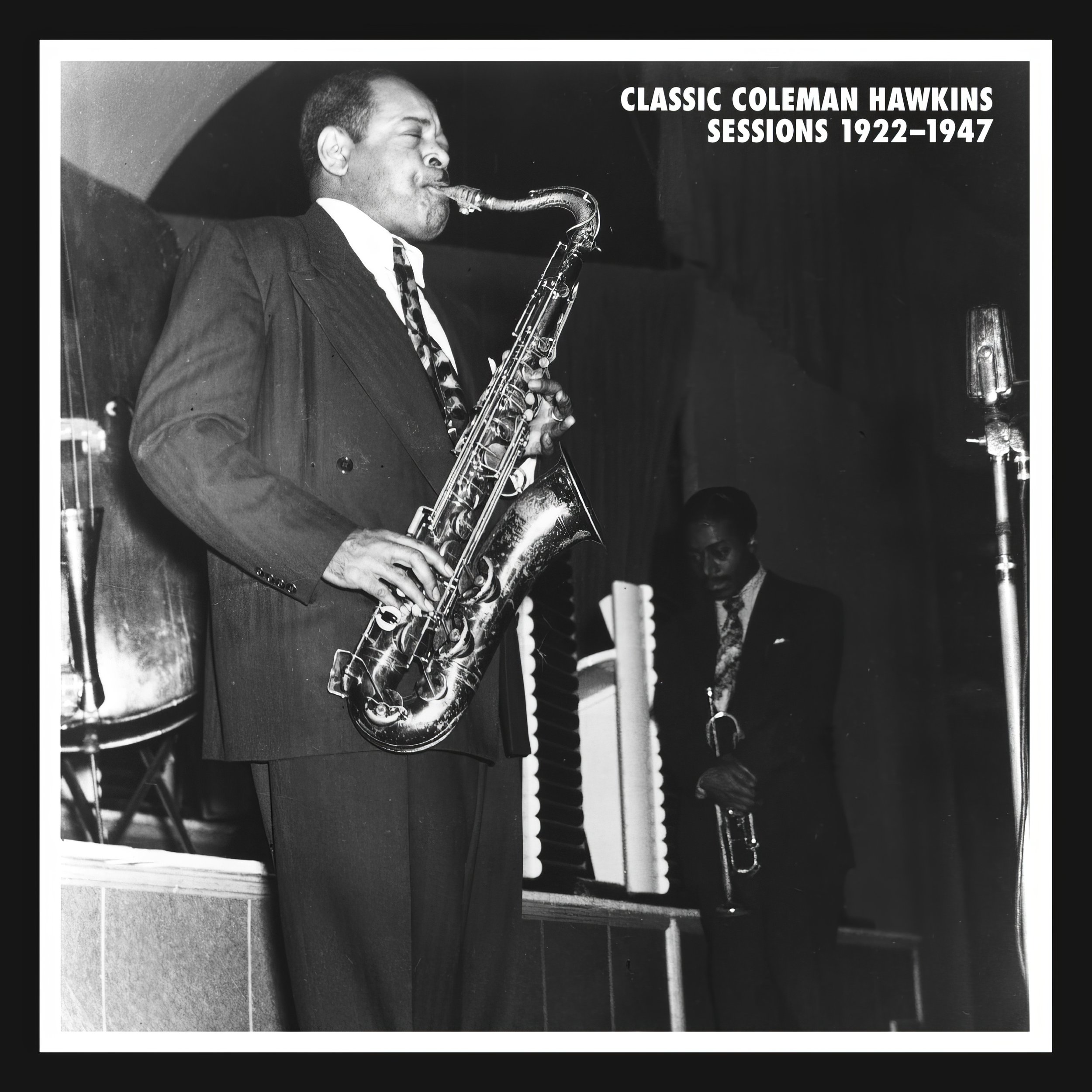

Classic Coleman Hawkins Sessions 1922-1947

“We all had our mentors. From whom did Hawkins copy? I don’t think he copied anybody. He was a creator. He led.”

Benny Carter

“It was unnerving how intently he could listen. You’d be playing and suddenly you’d be aware of someone standing off to your right. If you looked over, you’d see him with his arms folded and his head down just a little, watching and listening to everything. He did that for as long as I knew him.”

George Duvivier

“A young tenor player was complaining to me that Coleman Hawkins made him nervous. Man, I told him Hawkins was supposed to make him nervous! Hawkins has been making other sax players nervous for forty years!”

Cannonball Adderley

“The wildcat’s loose!”

Fletcher Henderson

Coleman Hawkins single-handedly created the idiom for the tenor saxophone in jazz. Before he came to maturity, Sidney Bechet and Adrian Rollini had already taken giant steps on the soprano and bass saxophones respectively, establishing the idea that the saxophone could be used to make great jazz. It was left to Hawkins to process the innovations of Louis Armstrong in an intensely personal way, and fashion out of them his own voice.

There are very few musicians in any genre who remain protean figures for as long as Coleman Hawkins did. When he gave up the cello for the saxophone in the early 1920s, not only was his chosen instrument considered a joke at best, there was as yet no model for coherent jazz improvisation. Miraculously, at the age of 35 he would have a hit recording that remains one of the most sophisticated and challenging items ever to come remotely near the bestseller’s list. And by the age of 59 Hawkins would more than hold his own in studio encounters with John Coltrane and Sonny Rollins – both of whose careers would have been unimaginable without Hawkins’ precedent.

Coleman Randolph Hawkins was born in St. Joseph, Missouri, on November 21st 1904. There were many variations in African-American life during the early 20th century, though all too often the sort of poverty that Louis Armstrong experienced in New Orleans is thought to be endemic of how all black jazz musicians were raised at the time. Hawkins’ childhood was a comfortable and stable one, lived in relatively middle-class comfort. Young Coleman was given classical music lessons on the cello and also played the piano before settling on the saxophone as a teenager. The attractive tone of the cello and the harmonic world made explicit by the piano would greatly benefit him over the next decade and a half as he moved toward musical maturity. He continued to play the cello through his adolescent years as a student at the Industrial and Educational Institute in Topeka, Kansas, and doubled on the C-melody saxophone with local dance bands and in theater orchestras in nearby Kansas City.

Vaudevillian Mamie Smith was reveling in the acclaim generated by the huge success of her 1920 recording CRAZY BLUES when she came through Kansas City on a tour, supplementing her band with local musicians. The 16-year-old Hawkins immediately impressed her with his skills at both reading music and improvisation. Although Smith’s first attempts to take him on the road were rebuffed by Hawkins’ grandmother, his mother eventually granted permission several months later – only too happy to have a good excuse to force her son to part company with a certain local girl. The following year on the road with Smith’s troupe gave Hawkins a life’s worth of professional and personal lessons. He was by now concentrating mostly on the tenor saxophone, and though still a teenager, his incontestable mastery of the instrument made him a standout by the time he settled in New York in the summer of 1923. He soon came to the attention of bandleader Fletcher Henderson, who hired him for a series of recording sessions.

The early 1920s was a burgeoning time for jazz, and a virtuoso like Hawkins could make an excellent living by freelancing in nightclubs, playing theatre dates and recording. Henderson was eventually able to offer Hawkins full-time employment, and the saxophonist remained a featured member of the band for a decade.

Musically, there is little to distinguish the Hawkins of 1922-1924 from the other saxophonists of the time. He would spell out the basic chords, and articulate in a forceful manner known as slap-tonguing. It seems that his already growing reputation came more from his sheer volume and gusto, as well as his superlative skills as both a reader and a soloist. The arrival of Louis Armstrong in the Henderson band in late 1924 for a yearlong stint was to have a profound impact on the music world in general and on the 20year-old Coleman Hawkins in particular.

Armstrong created jazz phrases out of a vocabulary that drew heavily upon the blues and the “irrationalities” of African rhythms. This frightened some in the music world, and inspired up many more. Within a decade there would be Armstrong-esque singers and instrumentalists all over the world. Hawkins was one of the first to begin transforming Armstrong’s example into personal terms, but it would be a lengthy process.

One essential component of Hawkins' musical personality was his competitiveness. As soon as he heard about another saxophonist of any repute, there would be a jam session where, inevitably, Hawkins would predominate. This remained the case until one fateful Kansas City night late in 1933 when Lester Young countered every note that Hawkins aimed at him. In many ways, Young’s style was an inversion of that of Hawkins. Hawkins’ basic orientation was harmonic, whereas Young’s was indisputably melodic. When it came to up-tempo playing Young took his cue from Armstrong and would float as lightly as Hawkins trod heavily. And in terms of tone, where Hawkins was declamatory and fervent, Young seemed to be whispering and even, on occasion, just thinking his solos. What they shared was total originality and a seemingly limitless capacity for extended improvisation.

The Depression altered the entertainment business radically, and Henderson was having trouble finding steady work for his band as 1933 turned into 1934. In addition, since the departure of Armstrong in late 1925, Hawkins had been shouldering the great bulk of the band’s solo load. The sheer responsibility of having to do so night after night and year after year must have been wearying.

A chance encounter with ex-Hendersonite tubaist June Clark, who had just returned from an extended stay in Europe, led Hawkins to a contract with British bandleader Jack Hylton. He spent the next five years in Britain and on the Continent, appearing as a featured soloist with a succession of dance bands and radio orchestras, while recording prolifically. There had been other visits by great American jazzmen – most notably Duke Ellington, Sidney Bechet and Louis Armstrong – but none of them lived and worked among European musicians to the extent that Hawkins did.

During this period he wrote many letters, and they afford a fascinating insight into his complex character. First brought to light in John Chilton’s biography THE SONG OF THE HAWK, they show him to be a highly literate and compassionate observer of the human condition. Hawkins kept up on musical happenings in America through recordings and radio broadcasts, and had good things to say about Benny Goodman, Roy Eldridge and Duke Ellington, among others.

In Europe he recorded in settings ranging from duets with a pianist to big-band sessions. He even sang on occasion, something he never did again. One session that has attained classic status took place in 1937, when Hawkins was reunited with his former Henderson bandmate Benny Carter (also living in Europe) alongside the Belgian gypsy guitarist Django Reinhardt. OUT OF NOWHERE and CRAZY RHYTHM contain definitive Hawkins solos, full of drive and harmonic sophistication, where he plays like a man possessed.

During his European years, Hawkins not only enjoyed a lifestyle he could not experience back home, but he also had the opportunity to play concerts where he could begin and end his pieces with long, out-of-tempo solos – which would have been impossible in the almost exclusively dance-based music he’d been playing with Henderson. Nonetheless, a desire to play once again with his peers back home, as well as the imminence of war in Europe, brought him back to the States in the summer of 1939.

What happened to Hawkins from that point through 1947 is covered in the music notes in this collection. The jazz impresario Norman Granz came into Hawkins’ life in the post-war years and was able to offer a healthy season of tours with the Jazz At The Philharmonic troupe – the first of which paired Hawkins with Lester Young. During the off times, Hawkins continued to appear as a single both in the States and abroad. In the 1950s he started an association with Roy Eldridge that was to last irregularly for the rest of his life. They made a great team, both on and off the bandstand. Hawkins was known to be sensitive about his age, which set the stage for all sorts of badinage with his bandmates. Stanley Dance captured a typical scene in his book The World Of Swing. “When the Eldridge-Hawkins Quintet was once playing the Heublein Lounge in

Hartford,” wrote Dance, “an eight-year-old girl insisted on getting the autograph of Coleman Hawkins, and his only. ‘How is it, Roy,’ he asked afterwards, ‘that all your fans are old people? They come in here with canes and crutches. They must be anywhere from 58 to 108. But my fans are all young, from eight to 58 years old!’ ‘That little girl thought you were Santa Claus,’ said drummer Eddie Locke. ‘Is that so? Well, who’s got more fans than Santa Claus?’”

One of the very best later Hawkins recordings is Coleman Hawkins And Roy Eldridge At The Opera House (1957). They are accompanied by pianist John Lewis, bassist Percy Heath and drummer Connie Kay. Two superlative studio sessions also appeared, made with Henry ‘Red’ Allen (including trombonist J.C. Higginbotham) and with Thelonious Monk (also featuring John Coltrane). And Hawkins played a major role in the best jazz TV show to date, The Sound of Jazz, broadcast live on CBS in 1957. One of its joys was the reaction of the other musicians when Hawkins played – and his solo on ROSETTA was particularly fertile.

Hawkins stoically weathered the advent of rock ’n’ roll and the attendant diminution of work for musicians of his generation. Caught in between fetishes for traditional jazz and “the new thing”, Hawkins only gradually got the kind of adulation and employment that was truly his due. He spent more and more time in his elegant apartment in New York City where he was surrounded by a world-class collection of classical music, with an emphasis on piano music and opera. Friends fondly recall the “musicales” Hawkins would host, always with superlative pianists (mostly from Detroit) present. He formed a quartet with just such a pianist, Tommy Flanagan, alongside Major Holley and drummer Eddie Locke, and they recorded some outstanding albums for Impulse Records, as well as working sporadic live dates.

An appearance with his disciple Sonny Rollins at the 1963 Newport Jazz Festival also spawned a record date, for RCA Victor. Rollins pulled no punches; after all, Hawkins was known for his love of the civil-but-very-serious cutting session. The younger man unleashed a barrage of eccentric, expressive devices, challenging Hawkins to re-assert the levels of creativity that had established him in the first place. What resulted was a vivid image of the late Hawkins’ true identity as improviser, made starker by the startling context in when Rollins placed him.

As he approached his mid-60s, Hawkins began to fall apart. For four decades he had been renowned for his sartorial splendor. Now he seemed indifferent to how he looked. The music also suffered as he stopped supplementing his heavy drinking with the food necessary to act as ballast for the alcohol. Hawkins eventually grew a beard that in its unkempt state made him look like a latter-day Methuselah. Friends including Thelonious Monk and, notably, Eddie Locke did their best to steer him off this course of self-destruction, but to no avail.

His musical instincts never faltered, and until his body gave out, he was capable of scaling the musical heights he had long inhabited. Was it his father’s suicide in the 1930s that laid the groundwork for those sad last few years, or was it his inability to find a place for himself in a jazz world where the technical and professional skills he prided himself on were no longer deemed necessary? The fact remains that Coleman Hawkins died on May 19th 1969, just days after a final concert with Roy Eldridge. The vast majority of his life was spent spreading joy through his intense and intricate music that he played with unfailing integrity. As all great jazz musicians, Hawkins explored and helped define the area where the best attributes of composition and improvisation intersect, and all of us remain eternally in his debt.